Chapter 1 Background

Every one knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in a clear and vivid form of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal with others

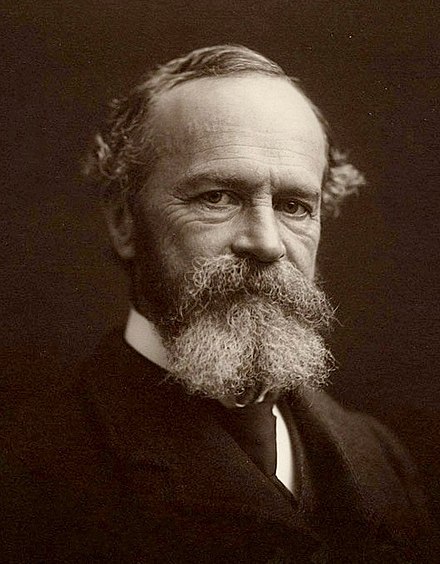

That was William James, one of the founders of modern psychology, writing in 1890, which was the very beginning of the scientific study of psychology. In the quote, he appeals to common sense. Common sense was relevant because some things about attention have been understood for a very long time, even if not studied scientifically.

The Cardsharps was painted by Caravaggio more than four hundred years ago. It depicts a young man getting duped in a card game by two cardsharps. The cardsharp in front is assisted by an older man who looks over the victim’s shoulder. That guy in the back signals something about the cards to the younger cardsharp, who reaches behind his back to pull a new card from his breeches.

Clearly people of that time knew how to manipulate the attention of others so that they would notice some things and not others. And I don’t mean just cardsharps; in order to create paintings that would direct the viewer’s attention in the way he intended, painters also understood various things about attention.

Much of the knowledge of attention possessed by painters, and by con men like cardsharps, was likely implicit rather than as spelt out as we expect for a scientific theory. It was only in the twentieth century that scientists began doing extensive experimentation on attention, and even then attention was studied very little relative to memory, perception, or cognition.

Around the 1970s, that began to change, but there is still much for science to learn about attention. A good starting point continues to be common-sense understanding of attention - what is sometimes called folk psychology. Some aspects of this are old enough that they have become embedded in our language. For example:

- Please “pay attention!”

- Implies that one has to choose something (often the teacher) to fully process its signals.

- “Sorry, I wasn’t listening”

- In English, there’s a difference between hearing something and listening to it. Not listening means although it may have been processed by our ears, we either didn’t experience it or didn’t retain it.

- “Sorry, I missed that.”

- People sometimes say this after someone else says something and the first person realizes that they didn’t understand what was said. In particular, people say it when they don’t think the problem was that the statement was not loud enough for them to hear. Instead, the problem is often something with attention.

- “I didn’t notice that.” What do you think people might mean when they say that rather than choosing to instead say “I didn’t see that.”?

Failures to notice things explain a substantial proportion of accidents such as car crashes. But why do we have to pay attention to comprehend or retain some information? That is the subject of two coming chapters (3, 4).

If you took PSYC1 at the University of Sydney, you already heard Caleb Owens’ “Cognitive Processes 2” lectures on visual attention, which were related to what you will learn here. Caleb’s lectures had the following learning outcomes:

- Understand and be able to give examples of situations where focused visual or auditory attention leads to limited processing of other stimuli.

- Be able to define, distinguish and give examples of focused attention, divided attention, diffused attention, inattentional blindness, and change blindness.

- Understand and be able to describe the difference between an early, late or flexible locus of selection.

- Be able to both give and interpret examples which demonstrate an early, late or flexible locus of selection.

- Be able to define and distinguish between endogenous and exogenous attention

- Understand the role of attention according to Treisman’s FIT (feature integration theory) and the visual search evidence (for both feature and conjunction targets) which supports it.

This year has its own list of learning outcomes (2).

We will review material from Caleb’s lecture, bring new ideas to bear on it, and add more material. In the parts that review Caleb’s points, we will go quickly.

_-_The_Cardsharps.jpeg)