Social factors

Two thousand years ago, Aristotle wrote: “Man is by nature a social animal.” He was right — people are very interested in people, and in working out what they’re thinking and feeling. There are evolutionary reasons for this. We live in groups and like us, our ancestors depended on each other not only for mating opportunities, but also to survive.

This aspect of our nature shows up in what we choose to look at. In a previous chapter (4), you learned that most movements of attention are overt. If people are interested in something, they usually will look right at it.

Once researchers were able to record eye movements, they asked study participants to look at pictures of scenes. If there were people depicted in the scene, rather than looking mainly at parts of the scene that were salient due to bottom-up factors, such as colors or shapes that stood out by being unique, the participants tended to spend a lot of time looking at the people.

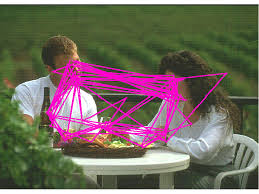

One scene researchers have collected data for is the dinner date change blindness scene.

Specifically, the eye movements of people were recorded while they were viewing the animated blank screen sandwich, to see where people look.

Pink lines indicate the trajectory of eye movements made by people searching for a change.

The above image shows some eyetracking data for one participant. The long straight lines represent big jumps of the eyes from one place to another as the participants tried to determine what was changing. As you can see, the eyes dwell mostly on the couple’s faces, their hands, and some objects on the table. So, the locations that people looked were not random at all, and frequently did not occur in left-to-right reading order.

Remember that the task of the participants was to detect what was changing in the scene, which was presented in blank-screen sandwich format. The participants presumably understood that the change could be anywhere in the scene, but the data shows that they barely looked at the background, the bush in the foreground, or the railing (which was what was actually changing in the change blindness animation). Rather than taking a systematic approach of moving their eyes across the screen bit-by-bit, this participant (and many others) gave in to their bias to focus on the people.

Things like people and bodies are sometimes referred to as a scene’s high-level properties. The word “high-level” is used in part to indicate that those properties take more processing to extract, and thus are represented at later (“higher level”) stages of the brain compared to, say, color. The same is true of objects like food and wine. They are not recognized as objects (as opposed to as meaningless collections of colors and edges) until the temporal lobe, after many stages of visual processing.

Many of the study participatnts likely were interested in understanding the “meaning” of the scene, which involves working out the facial expressions of the people and how they are interacting with each other, based on their postures and the objects in front of them. If so, you might be like one of those participants (this is just an idea, NOT a validated psychological finding).

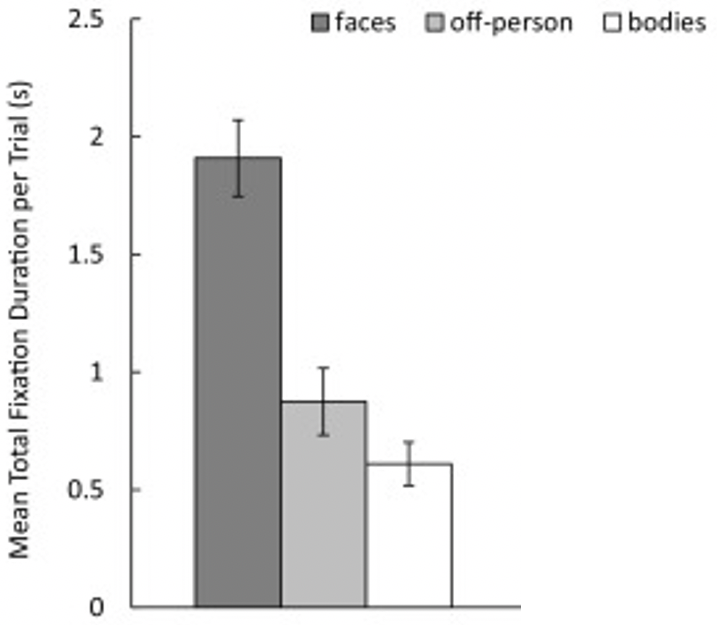

The above image shows the data for only one particular scene. Does the pattern of fixating the eyes more on face and bodies hold for other stimuli as well? Rigby, Stoesz, and Jakobson (2016) investigated this issue. Sixteen participants watched twelve four-second movie clips and twelve still-frame images from several episodes of a TV show that was heavy on dialogue and characters (the Andy Griffith show). The soundtrack was turned off during the viewing.

Average amount of time spent looking at different parts of the scene.

The results, shown above, provide further support for the hypothesis that attention is biased towards faces. In another study, Rösler, End, and Gamer (2017) flashed pictures of scenes for just a fifth of a second, so people had time for only one eye movement, and found that people disproportionately looked at parts of the scene with faces or bodies.

These social biases of attention are used by web app and advertisement designers who seek to control what you attend to. You may have noticed that many ads have a picture or animation of a person in them, even when this is completely unnecessary and superfluous to the information provided. It’s kind of hack of your attentional system to get you to read or watch ads.

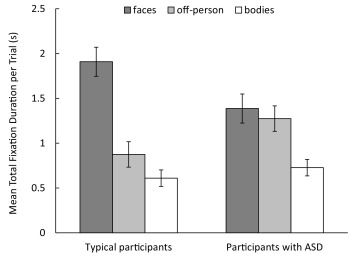

There is some evidence that the attention of many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is less biased towards faces than is that of typically-developing children. The study whose results are plotted above was one study that investigated this, by also including among their participants a group of sixteen adults with autism spectrum disorder.

Average amount of time spent looking at different parts of the scene, in sixteen adults with (right) and without (left) autism spectrum disorder.

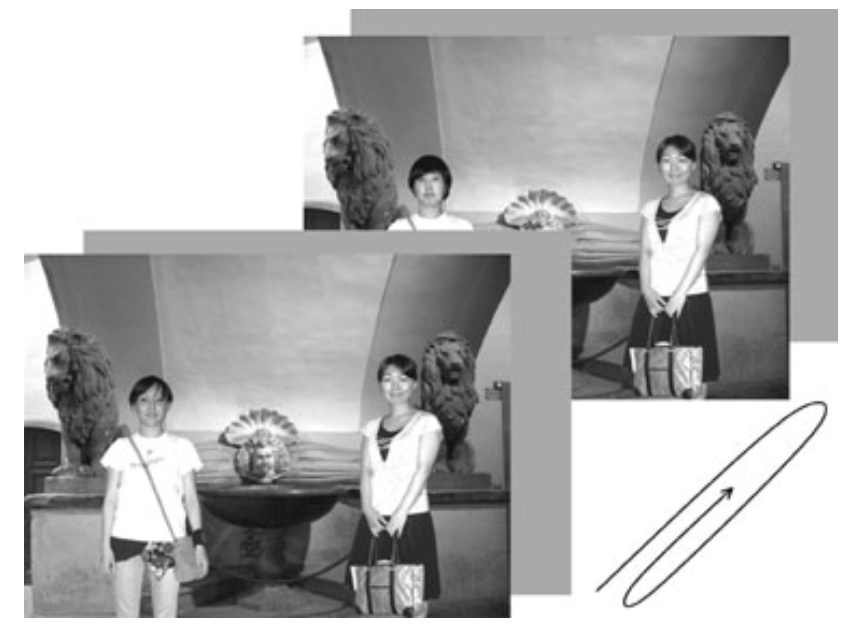

Based on this study, children with ASD don’t spend as much time looking at faces. What would you expect, then, for the pattern of performance in change blindness in people with autism spectrum disorder? Kikuchi et al. (2009) conducted a change blindness experiment and varied whether what changed was the head of a person, another object, or a change to the color of the background.

A schematic of one of the trials in the experiment. This trial is an example of the head change condition. The head of the person to the left was replaced by another head.

The blank screen sandwich was looped until the participants pressed a key. The participants were then required to report what the change was, by pointing at it or with a verbal description. As one measure of performance, the researchers examined only those trials where the participants correctly detected the change and plotted the response time on those trials. Shorter response times indicate that the person detected the change faster.

Other factors

One shouldn’t assume that people will always look primarily at the faces in a scene before looking at other things. When cycling or driving somewhere, there are times where it is important to keep our eyes on the road, such as when approaching a roundabout. At such times, most of us do not take our eyes off the road to linger on the faces of pedestrians or the drivers of other cars. At the same time, if we are bumper-to-bumper in a traffic jam, we might spend more time looking at the people in nearby vehicles.

Evidently our brains flexibly change visual priorities based on our interests and the demands of the task we are engaged in. Of course, this is not perfect, as we’ll discuss in Chapter 16.

Exercises

- Why do people need to move their eyes for many searches?

- What factors can make visual search slow?

- Describe how the kinds of selection connect to visual search performance for different types of display - learning outcome #5 (2).

- How does the finding for visual search performance for feature conjunctions relate to the rate limit found for pairing simultaneous features in the previous chapter?

Kikuchi, Yukiko, Atsushi Senju, Yoshikuni Tojo, Hiroo Osanai, and Toshikazu Hasegawa. 2009. “Faces Do Not Capture Special Attention in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Change Blindness Study.” Child Development 80 (5): 1421–33.

Rigby, Sarah N., Brenda M. Stoesz, and Lorna S. Jakobson. 2016.

“Gaze Patterns During Scene Processing in Typical Adults and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 25 (May): 24–36.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.01.012.

Rösler, Lara, Albert End, and Matthias Gamer. 2017.

“Orienting Towards Social Features in Naturalistic Scenes Is Reflexive.” PLOS ONE 12 (7): e0182037.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182037.

Chapter 10 Social factors

Two thousand years ago, Aristotle wrote: “Man is by nature a social animal.” He was right — people are very interested in people, and in working out what they’re thinking and feeling. There are evolutionary reasons for this. We live in groups and like us, our ancestors depended on each other not only for mating opportunities, but also to survive.

This aspect of our nature shows up in what we choose to look at. In a previous chapter (4), you learned that most movements of attention are overt. If people are interested in something, they usually will look right at it.

Once researchers were able to record eye movements, they asked study participants to look at pictures of scenes. If there were people depicted in the scene, rather than looking mainly at parts of the scene that were salient due to bottom-up factors, such as colors or shapes that stood out by being unique, the participants tended to spend a lot of time looking at the people.

One scene researchers have collected data for is the dinner date change blindness scene. Specifically, the eye movements of people were recorded while they were viewing the animated blank screen sandwich, to see where people look.

The above image shows some eyetracking data for one participant. The long straight lines represent big jumps of the eyes from one place to another as the participants tried to determine what was changing. As you can see, the eyes dwell mostly on the couple’s faces, their hands, and some objects on the table. So, the locations that people looked were not random at all, and frequently did not occur in left-to-right reading order.

Remember that the task of the participants was to detect what was changing in the scene, which was presented in blank-screen sandwich format. The participants presumably understood that the change could be anywhere in the scene, but the data shows that they barely looked at the background, the bush in the foreground, or the railing (which was what was actually changing in the change blindness animation). Rather than taking a systematic approach of moving their eyes across the screen bit-by-bit, this participant (and many others) gave in to their bias to focus on the people.

Things like people and bodies are sometimes referred to as a scene’s high-level properties. The word “high-level” is used in part to indicate that those properties take more processing to extract, and thus are represented at later (“higher level”) stages of the brain compared to, say, color. The same is true of objects like food and wine. They are not recognized as objects (as opposed to as meaningless collections of colors and edges) until the temporal lobe, after many stages of visual processing.

Many of the study participatnts likely were interested in understanding the “meaning” of the scene, which involves working out the facial expressions of the people and how they are interacting with each other, based on their postures and the objects in front of them. If so, you might be like one of those participants (this is just an idea, NOT a validated psychological finding).

The above image shows the data for only one particular scene. Does the pattern of fixating the eyes more on face and bodies hold for other stimuli as well? Rigby, Stoesz, and Jakobson (2016) investigated this issue. Sixteen participants watched twelve four-second movie clips and twelve still-frame images from several episodes of a TV show that was heavy on dialogue and characters (the Andy Griffith show). The soundtrack was turned off during the viewing.

The results, shown above, provide further support for the hypothesis that attention is biased towards faces. In another study, Rösler, End, and Gamer (2017) flashed pictures of scenes for just a fifth of a second, so people had time for only one eye movement, and found that people disproportionately looked at parts of the scene with faces or bodies.

These social biases of attention are used by web app and advertisement designers who seek to control what you attend to. You may have noticed that many ads have a picture or animation of a person in them, even when this is completely unnecessary and superfluous to the information provided. It’s kind of hack of your attentional system to get you to read or watch ads.

There is some evidence that the attention of many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is less biased towards faces than is that of typically-developing children. The study whose results are plotted above was one study that investigated this, by also including among their participants a group of sixteen adults with autism spectrum disorder.

Based on this study, children with ASD don’t spend as much time looking at faces. What would you expect, then, for the pattern of performance in change blindness in people with autism spectrum disorder? Kikuchi et al. (2009) conducted a change blindness experiment and varied whether what changed was the head of a person, another object, or a change to the color of the background.

The blank screen sandwich was looped until the participants pressed a key. The participants were then required to report what the change was, by pointing at it or with a verbal description. As one measure of performance, the researchers examined only those trials where the participants correctly detected the change and plotted the response time on those trials. Shorter response times indicate that the person detected the change faster.

Figure 10.1: Mean correct response time for detecting a change. The black line represents children with ASD and the dashed gray line typically developing children. Error bars are one standard error.

10.1 Other factors

One shouldn’t assume that people will always look primarily at the faces in a scene before looking at other things. When cycling or driving somewhere, there are times where it is important to keep our eyes on the road, such as when approaching a roundabout. At such times, most of us do not take our eyes off the road to linger on the faces of pedestrians or the drivers of other cars. At the same time, if we are bumper-to-bumper in a traffic jam, we might spend more time looking at the people in nearby vehicles.

Evidently our brains flexibly change visual priorities based on our interests and the demands of the task we are engaged in. Of course, this is not perfect, as we’ll discuss in Chapter 16.

10.2 Exercises