Chapter 13 The role of memory and expectation

13.1 The contents of memory can guide attention

13.1.1 Working memory

Working memory refers to information that you currently have in mind, often long-term memories that you are “working” with at the moment and thus may be present in consciousness. As far back as 1893, it was suggested that “Impressions which repeat or resemble ideas already present in consciousness are especially liable to attract the attention” (Külpe 1893), which was an early way of saying that having something in one’s working memory can guide attention to associated sensory stimuli.

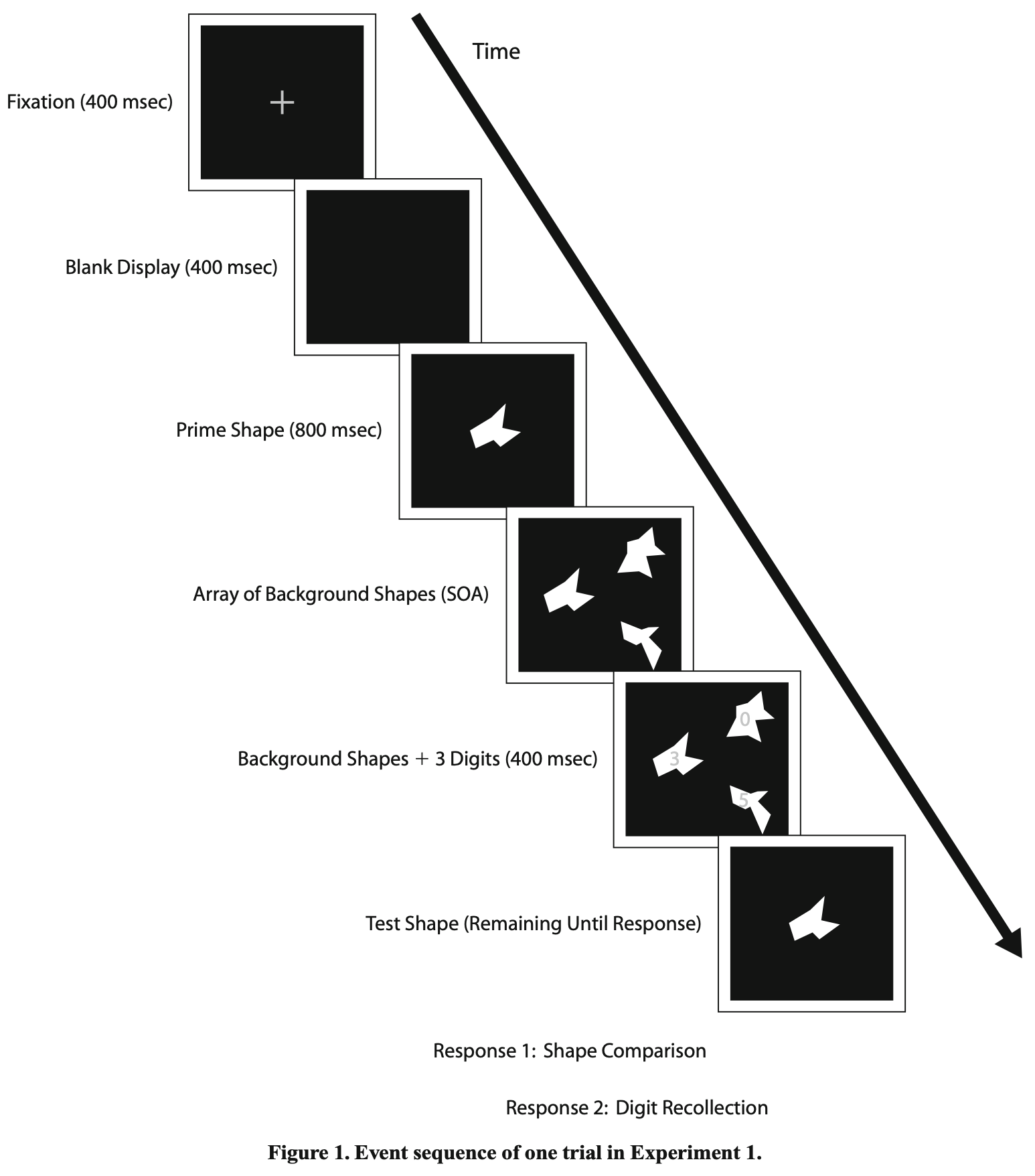

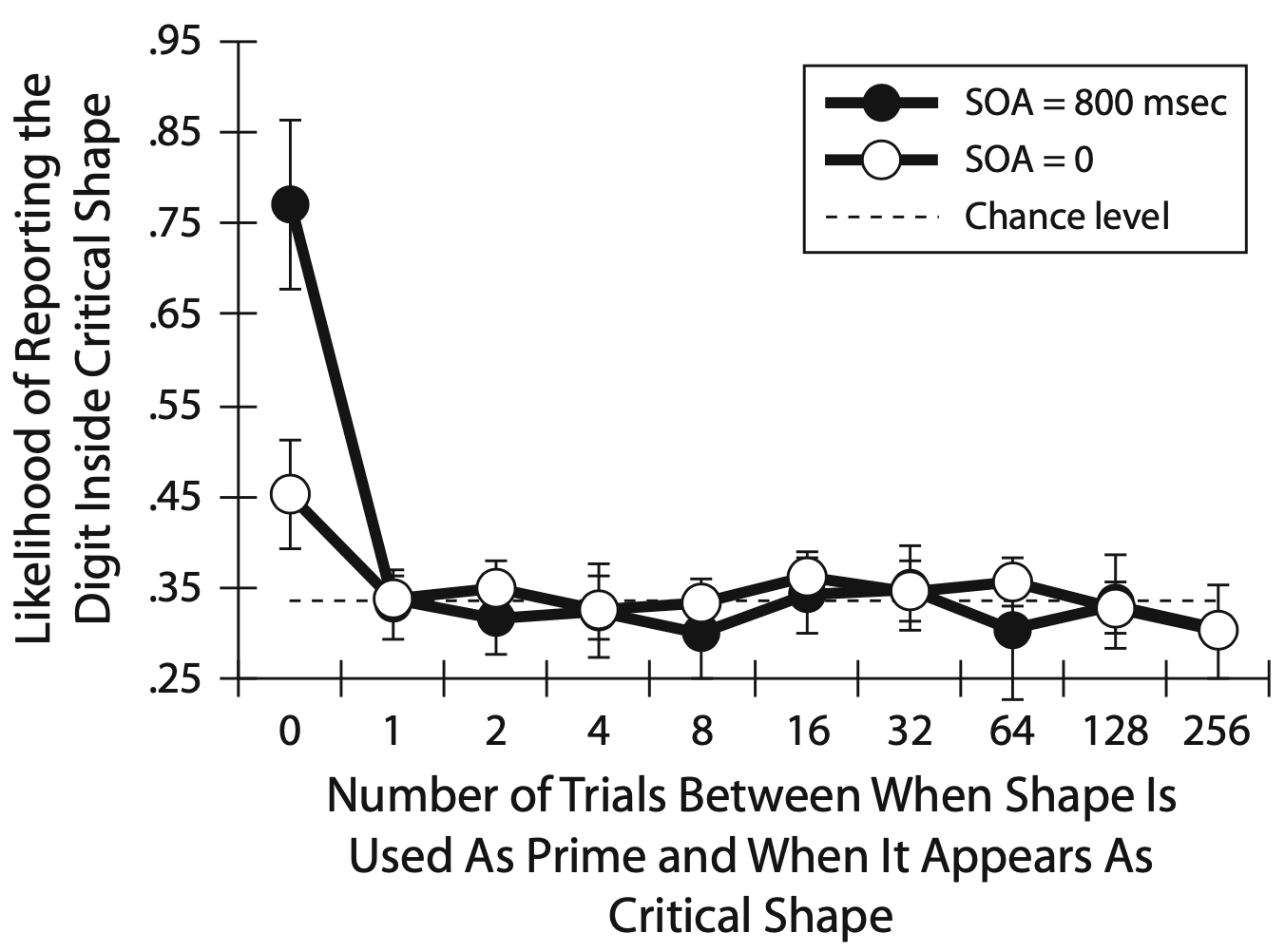

Huang and Pashler (2007) did an experiment that provided quantitative evidence for Külpe’s claim. Participants had to memorize a shape (the “prime shape”), knowing at the end of the trial they’d see a shape and be asked whether it was the same one. They also knew that after the prime shape was presented, they’d be presented with three digits that they should memorize because they’d be asked to report them at the end of the trial.

The digits to be memorized were presented on a background of three shapes, and critically, one of those three shapes had been presented previously as a prime shape to be memorized. On 10% of trials, that previously-memorized shape was also the shape to be memorized for the current trial. The hypothesis was that if having a shape in mind guided attention, then people would do better at reporting a digit that was presented on that trial’s prime shape than at reporting other digits.

The results show that if the shape that a digit was presented in the prime shape for that trial, people did well at reporting that particular digit. But if the shape had instead been presented on a previous trial, performance was indistinguishable from the level one would find if the participant simply guessed the digit. This pattern of results shows that holding a shape in mind (the prime shape) caused participants to attend more to that shape (and the digit presented on it) subsequently.

- When there was no time from background shape onset to digit onset (0 SOA), performance was not nearly as good as when the background shapes were presented for 800 milliseconds before the digits came on. Why might that be?

13.1.2 Long-term memory

That the contents of long-term memory may also guide attention is suggested by the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, which is also known as the “frequency illusion.”

Read this article about it.

- Why is it called the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon?

Zwicky theorized that an important cause of the phenomenon is an aspect of attention. As Huang and Pashler (2007) showed, once you have something in mind, you pay more attention to it when you encounter it. The Baader-Meinhof effect suggests that this phenomenon extends to things you recently learned about. Once you know about something, such as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, it’s more likely that you’ll pay attention to and thus remember any individual encounter with it.

13.2 Apollo Robbins, misdirection, and pickpocketing

Magicians use their knowledge of how attention works to prevent us from noticing things that are right in front of us, in the real world, not just in a laboratory experiment video.

Watch Apollo Robbins talk about misdirection.

- What does he say about attention?

Now, watch again the sleight of hand trick he does in that video (I’ve set the video to begin playing at the critical part). How did the pen end up behind his ear?

Sometimes the movements that disappear objects in a magic trick are highly visible, but because our eyes and/or attention were in the wrong place, we don’t notice them.

Watch this video of Apollo performing sleight of hand and pickpocketing.

- How does Apollo manage to repeatedly place the coin on the woman’s shoulder without her attending to her shoulder?

If the women could replay all the arm and hand movements of Apollo in her head, she could perhaps work out how the coin got on her shoulder. Unfortunately for them, they don’t remember them all, because of a combination of the attentional bottleneck and the memory bottlenecks, not many of the movements got into memory. And when the movements were actually happening, Apollo subtly led the women to believe that the critical ones were unrelated to the coin.

- What role does eye-gaze cuing play in Apollo’s video?

Optional reading: A NYT article about magic.

13.3 Four factors for managing attention

Apollo used the following four things to manage people’s attention:

- Cuing

- By directing attention away from where the coin actually was, Apollo prevented the women from focusing attention on the critical movements.

- Expectation

- Apollo says things and makes gestures to cause viewers to expect something critical to occur in one location, so all eyes are on that location. This mostly happens via the viewers’ top-down attention. Meanwhile, the critical action is happening somewhere else.

- Engagement in a task

- When one is fully engaged in a task, bottom-up cues can be less effective in attracting attention. When one is not engaged in a task, one’s attention can be widely distributed, ready to go to a location indicated by a cue. Magicians like Apollo sometimes ask people to concentrate on something (while the critical event for the trick is happening somewhere else). Also, the magicians may keep telling the participants things to ensure their mind doesn’t wander in an unwanted direction.

- Encouragement to adopt a certain interpretation of an action

- For example, Apollo getting the participants to get used to and expect him to touch their shoulder, until they interpret it as just a touch rather than that he might be putting something on their shoulder.

The last factor listed above is more of a high-level cognition phenomenon than the basic attentional phenomena that are the focus of this class. Specifically, the interpretation of the actions is being shaped by an implicit cognitive schema or narrative. The sections above on how the contents of memory influence attention are a precursor to this. Narratives and stories shape our interpretation of many things in the world, from peoples’ body movements to news stories.

13.4 Inattentional blindness

You might have already seen some of the inattentional blindness movies in this section, but now you are equipped with some new ideas to apply to them. Keep the four factors (13.3) that manage attention in mind.

Inattentional blindness refers to people not noticing something that’s highly conspicuous if you know it might be coming, but is not conspicuous if you don’t. This is different from the change blindness videos and the pickpocketing demonstration. In the change blindness videos, people knew there was a large change happening somewhere in the scene, but it still wasn’t conspicuous. And in Apollo Robbins’ pickpocketing demonstration, people knew they were about to be pickpocketed.

People notice even fewer things if they aren’t expecting them, or if they’re given an unrelated task.

Watch this video for a demonstration and explanation (you can ignore the stuff about “smooth pursuit” at the end).

Take-aways:

- When you’re focused on the task of evaluating the kick, you don’t focus your attention on other things.

- The constant motion of the cheerleaders helped prevent the changes from grabbing your attention.

- Because noticing changes is capacity-limited, not having one’s attention on the change meant it wasn’t encoded or noticed.

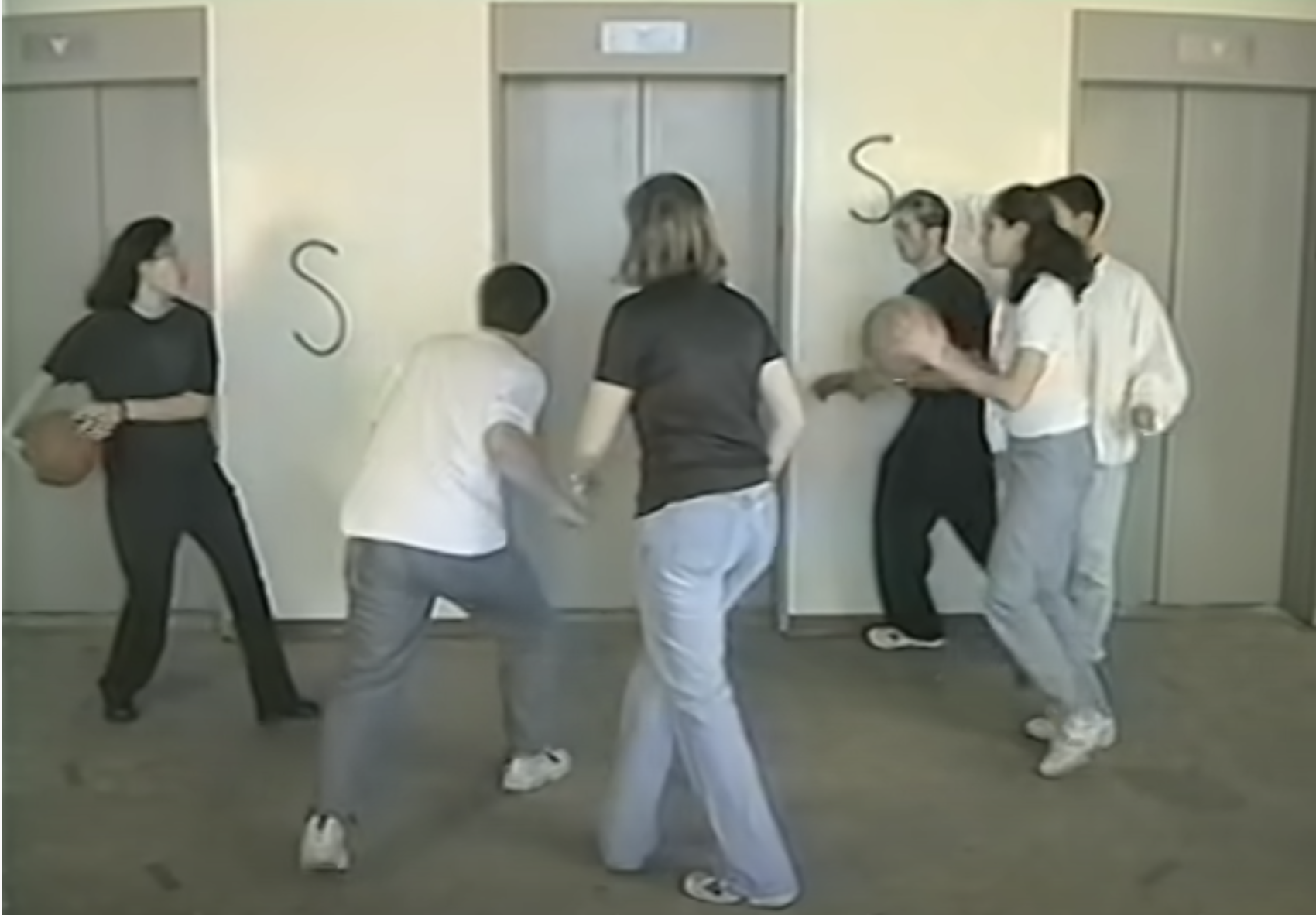

The most classic demonstration of inattentional blindness involves the video created for an experiment by D. J. Simons and Chabris (1999). When watching the video, your task is to count the number of times the people in white shirts pass the basketball. Watch the video here.

Many of you may have seen that video before, which can create some expectation of what would happen and helped you notice what many people miss the first time they watch the video.

The associated experiment was done in 1999. The participants’ task was to count the number of passes of either the white-shirted or black-shirted team. Doing the basketball task made their minds less likely to notice anything not basketball-related. It was as if they were “blind” to the gorilla in the scene - hence the name of the phenomenon, “inattentional blindness”. The participants weren’t expecting to be asked about anything besides their count of basketball passes, so all their attention was oriented towards the basketball task.

They were much more likely to notice the gorilla if they were counting the passes of the black team than if they were the white team. This is an example of the effect of feature selection. In one version of the experiment, only 42% noticed the gorilla if they were counting the passes of the white team, while 83% did if they were counting the passes of the black team!

13.4.1 The failure of bottom-up attention in inattentional blindness

These findings of inattentional blindness do not mean that people, when focused on a task or not expecting something, will never notice other things. Bottom-up attentional cues such as sudden flashes or sounds will still usually be effective in grabbing someone’s attention. But in most of the inattentional blindness videos and experiments, the displays are arranged so that the cues are not very effective. For example, in the gorilla video there was lots of motion throughout the scene. If the gorilla had been the only thing moving in the scene, everyone would have noticed it, thanks to bottom-up attention.

13.4.2 The door swap

One of the funniest inattentional blindness demonstrations is the door swap. Watch this version created by Derren Brown.

In the Derren Brown video, it seems clear that some people definitely didn’t notice the swap, and it’s pretty amazing if even only a minority of people didn’t notice the swap. However, to make the video more amazing, the TV program producers may have edited the video to omit some cases of people who did notice and say something when the person changed. Because of such hijinks, you should always be suspicious of TV shows and Youtube videos!

From the Daniel J. Simons and Levin (1998) article reporting the original scientific study, we knew that in the main study, seven of fifteen participants reported noticing that the person changed. That’s not as incredible as the impression one gets from the Derren Brown video, but still it seems amazing that eight of fifteen people did not notice the person changed. The experimenters were initially worried that perhaps those people did notice, but were too shocked, embarassed, or weirded out by the swap to say anything. For that reason, the experimenters took the people aside afterward to ask them whether they noticed anything strange. The results of this and other studies supported the idea that many people don’t notice such changes. You can watch excerpts of the study here.

Go back to the chapter on explaining two-pic change blindness (6). Which necessary processes for change detection do you think failed to occur?

What factors do you think contributed to the participants not noticing the surprising event in the door study?

What might be different between the people that did notice and the people who didn’t notice?

13.4.3 In the air

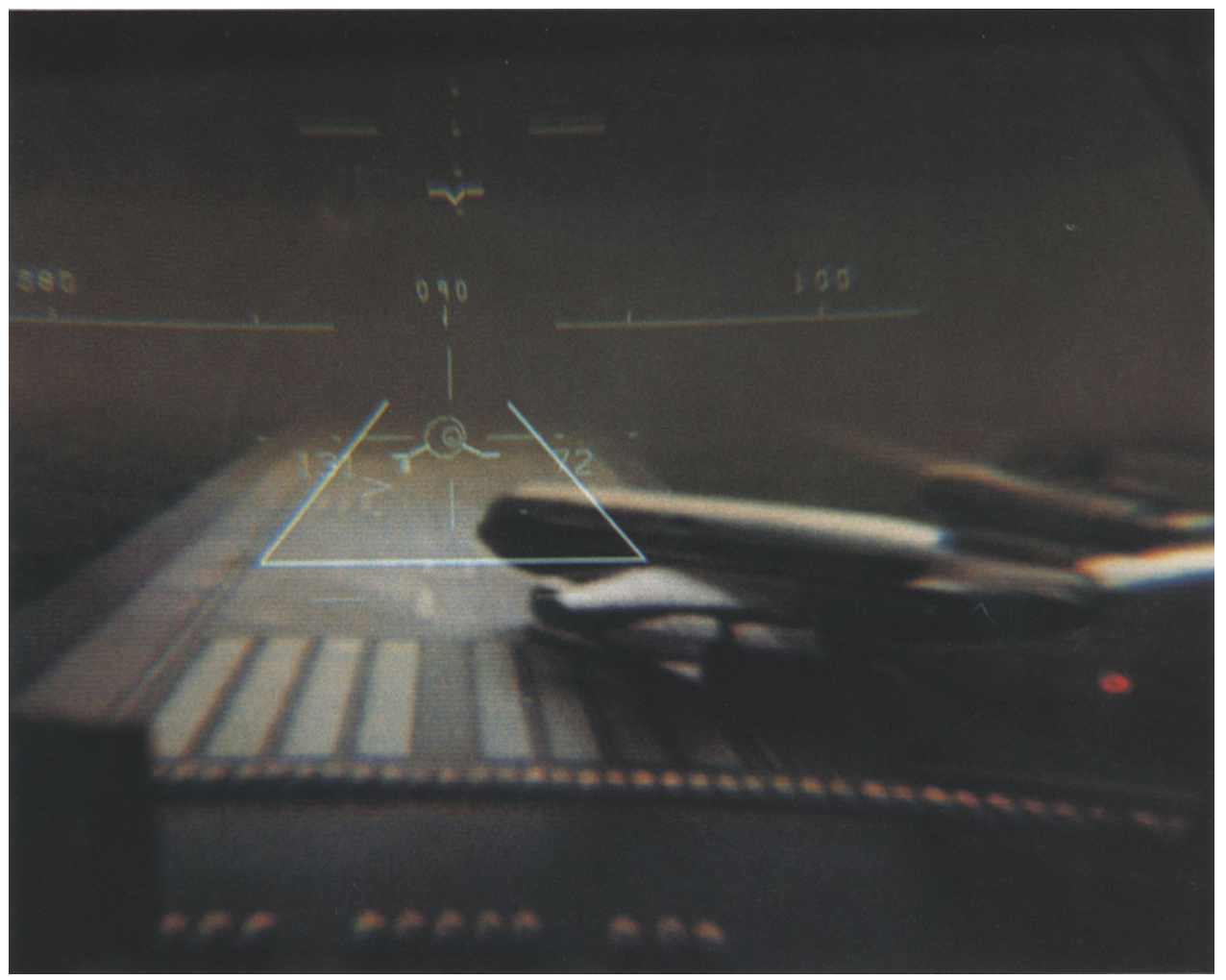

Inattentional blindness also occurs in the real world. Landing a plane is a demanding task that involves monitoring several instruments, even if cockpit designs are better than in the 1960s (3.2). Haines (1991) found that when landing in foggy conditions in a flight stimulator, several pilots did not notice a large airplane obstructing their path on the runway, one that was clearly visible as they approached:

The pilots’ strong engagement in the task of attending to their instruments probably contributed to some of them not noticing the plane. Indeed, narrow task engagement is a factor that frequently contributes to accidents. This is the third factor mentioned in 13.3 that can be used to manage someone’s attention.

Inattentional deafness is also a thing. People sometimes do not notice important sounds when they are not expecting them or they are highly engaged in a task. Optional: read this article on pilots not hearing alarms.

13.4.4 Exercises

- Why do bottom-up attentional processes fail to reliably draw attention to the gorilla in the D. J. Simons and Chabris (1999) video?

- What is the key characteristic that differentiates inattentional blindness from change blindness?

- Chapter 5 mentioned that being touched can easily draw your attention. This is a problem for pickpockets and magicians. How does Apollo Robbins solve this problem?