Chapter 14 Bottleneck - memory (INCOMPLETE)

What does it take to form a memory?

If I ask you about your memory, you’ll probably assume that I’m asking you about things pretty far in the past.. a different day, at least. But memory is required even for you to report something you saw a few seconds ago. In the laboratory, researchers have devised situations in which you will occasionally forget things that happened just two seconds ago.

One thing researchers do in their experiments is show people random, unrelated stimuli. That way, people can’t use their knowledge of the way the world usually works to reconstruct what must have happened. In the real world, if I hear the doorbell ring and ten seconds later find myself holding a package addressed to me, I can guess that probably what happened is I went to the door and got the package there. These standard sorts of sequences of events can help our brains reconstruct events in an act of remembering based on only fragments.

Another thing that researchers do is present stimuli only briefly. Let’s say I ask you to remember a photo like this.

As you examine the photograph, various descriptions may come to your mind. For me, I notice the white and black pincer-shaped wing markings, and the fuzz-tipped feathery wings blending into a fuzzy body. You might start making various associations, like with an eagle’s talons for the wing markings, a stuffed animal for the body, and a fur coat for the white edges of the wings. The longer you look at it, the more details you notice and think about, which creates more and more bits of memory that later can help you remember the image.

However, if you are shown an image only very briefly, then you have less chance to form memories about it. The twin features of brief presentation and unrelated stimuli are what help researchers probe how memory works even at the short timescale of seconds.

In most memory experiments, the stimuli are much more boring than my photo of the moth I showed you above. This is mainly for standardisation purposes, so that stimuli are similarly memorable and thus can easily be swapped with similar results obtaining. For example, often the stimuli are individual letters.

Below is an example movie with a rapid series of letters presented. When you watch the movie below, look out for and try to remember the letter that is circled.

If the movie didn’t work, you can watch it here.

Hopefully you were able to see which letter was circled. However, the act of trying to remember that letter can impair your memory of subsequent letters in the stream.

14.1 The attentional blink

Researchers have investigated the limitations on memory processes by asking people to remember more than one of a rapid series of images.

In the movie below, two letters are circled. Watch the movie and try to remember the circled letters.

If you can’t view the movie above, you can watch it here.

How did you do? If you’re good at the task, the above movie might have been too slow for you. In that case, try the one below.

If you can’t view the movie above, you can watch it here.

When Patrick Goodbourn and I investigated this in my laboratory (Goodbourn et al. 2016), we tested the performance of people when the two circles occurred at different times relative to each other. In particular, the second circle occurred at different lags after the first circle.

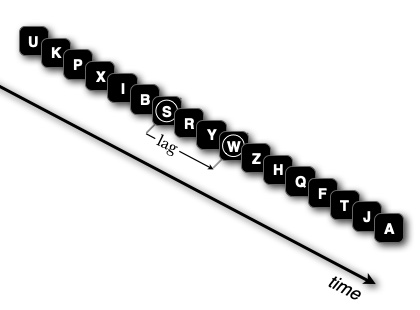

Schematic of a rapid sequence of letters, with a particular temporal lag between the two circled letters

At fast rates, most of the participants reported the identity of the first circled letter correctly about 60% of the time, regardless of the lag of the second circled letter. This is not too surprising - if a letter is presented too quickly, there often isn’t enough time for the visual system to fully process it before the next letter overwrites it. More interesting from a memory perspective was the pattern of performance for identifying the second letter.

When the lag was long, so that the second circle was presented a long time after the first circle, performance was about the same for reporting the second letter as for reporting the first. But when the lag was shorter, performance reporting the second circled letter was quite bad.

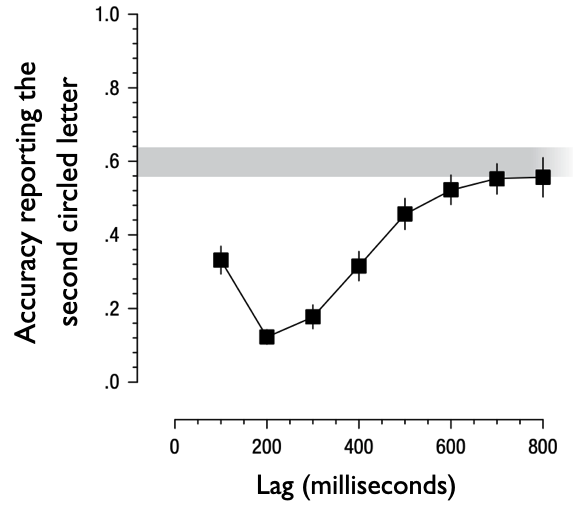

The vertical axis is the accuracy reporting the second circled letter, as a function of lag (only trials where the participants also got the first letter correct are included). They grey band shows the proportion of trials that average participants were correct for the first letter.

Notice that when the second circled letter occurred about 200 ms after the first one, people only got it right about 10% of the time. Performance stayed lower than for the first circled letter until the lag was over 600 milliseconds, a bit more than half a second. This phenomenon is called the attentional blink. It’s called the attentional blink because the researchers who documented it thought that the act of deploying attention to the first letter disrupted attention for several hundred milliseconds, preventing its deployment to the second letter.

In the years since its discovery, hundreds of experiments have been done on the attentional blink and these favor the idea that although attentional disruption may be one issue, a bigger problem is the time-consuming nature of memory consolidation. When the first letter is attended, your brain starts the processes of committing it to memory. This takes time, which mightn’t be a problem if it could process multiple events at once, but it can’t. That is, memory creation is subject to a bottleneck.

Previous chapters described the evidence for a bottleneck for judging two features of a single object (3.4 and 8).

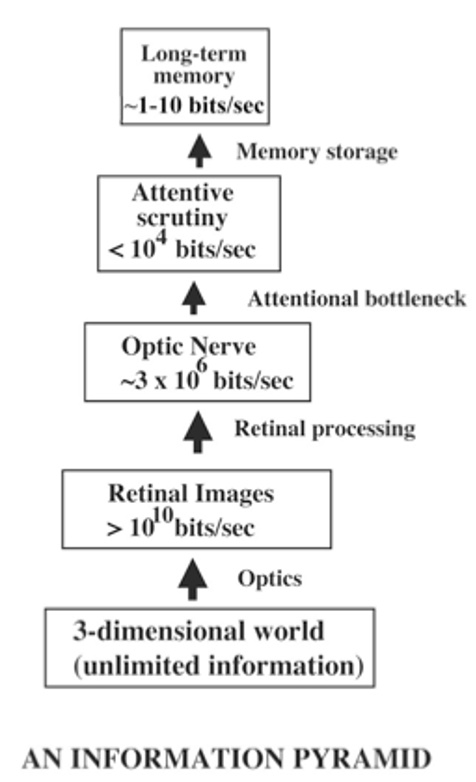

The attentional blink is thought to reflect a bottleneck situated after objects are processed. In the schematic below, the bottleneck for processing multiple features of an object would correspond to the “attentional bottleneck” and the bottleneck that causes the attentional blink would correspond to the “memory storage” process.

An estimate of the amount of information processed at successive stages of visual processing.

Memory involves three processes:

- Encoding - the sensory information must be successfully transferred into a durable representation.

- Storage - the encoded representation must be successfully stored until you need to retrieve it.

- Retrieval - the encoded representation must be successfully found in memory and retrieved.

Figure 14.1: Remembering something requires successful encoding, storage, and retrieval

In brains as well as in artificial neural networks, the three processes are highly intertwined, but still they are somewhat separate. The inability to report the second letter in the attentional blink is thought to be a failure of memory encoding. The idea is that while the brain is busy encoding the first circled letter, it is unable to encode the second letter because it cannot easily encode two things at a time. In other words, memory encoding is subject to a bottleneck.

Fortunately, the world is not made up of an unrelated series of events, such as rapid series of random letters. Things typically change gradually in the real world, so we have more time to encode things than do participants in an attentional blink experiment. Moreover, when things do change, the changes are often somewhat predictable. The brain can pre-activate expected information and get a head start on encoding them into memory. This is one reason that in the real world our encoding limitations are not as noticeable as in an attentional blink experiment.